Ethics in Performance Art

In my first post, I established that the tools of influence are a pharmakon: both remedy and poison. The line between a delightful surprise and a ruinous betrayal is often a moral fog.

But how does a perceptual architect know which one they are building? For those who construct immersive experiences, shape brand narratives, or design performances, navigating this landscape requires a robust ethical governor.

This is the precise function of the COVERT CAFE framework. While its COVERT diagnostic maps how perception is shaped, its CAFE governor provides the non-negotiable why and if.

The CAFE component defines four essential pillars: Consent, Autonomy, Foreseeable Consequences, and Exploitation.

This essay is a practical guide to implementing that ethical architecture, beginning with its foundation: Consent.

Consent: The Foundational Permission

Consent is the non-negotiable foundation for any experience that demands audience participation. In the world of immersive art, this presents a paradox: how does one gain informed consent for an experience that, to be impactful, requires a degree of unawareness? To detail the experience is to dull the discovery; to be vague is to void the consent.

I recently encountered an elegant solution at a burlesque cabaret. Upon seating, the usher provided a simple, laminated “Consent Disk.” One side was black, the other white. If the black side was visible, it signaled to performers that I was open to being approached and perhaps even touched. If the white side was up, I was left to watch, un-involved.

As someone who prefers to observe, this simple mechanic instantly removed any anxiety of being goaded into participation. This disk is a masterclass in ethical design because it reframes consent from a one-time, contractual waiver into an active, alterable state. It is an opt-in system, not an opt-out. It is easily understood, and the consent it grants is alterable at any time with a simple flip of the coaster. Most importantly, it demonstrates that a robust consent mechanism does not degrade the experience; it enhances it by ensuring the safety and respect of both the audience and the performer.

Autonomy: The Prerequisite for Choice

"The victim of mind-manipulation does not know that he is a victim. To him, the walls of his prison are invisible, and he believes himself to be free."

- Aldous Huxley

Autonomy is the first true consideration of ethical influence, as it is the prerequisite for consent.

If a person’s ability to make an informed, free decision is compromised, any “consent” they offer is meaningless.

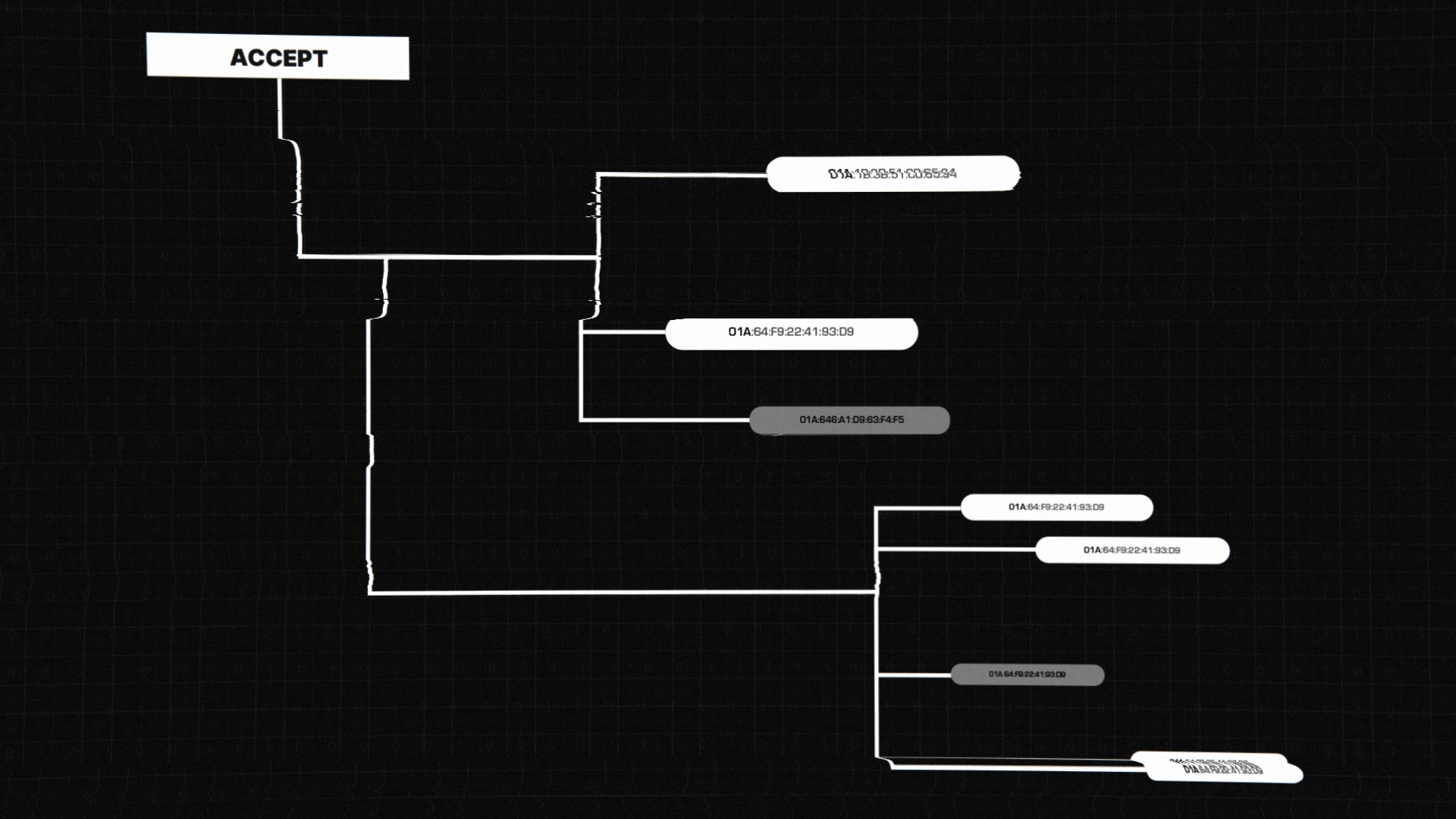

There is no clearer illustration of this than the “dark patterns” employed in digital design. These are user interfaces engineered to exploit cognitive biases and trick users into actions they would not otherwise take.

Let’s examine one of the most common: The “Hidden Cost” Tactic.

An individual booking a hotel online finds what appears to be a good rate. They “consent” to the purchase and begin the process. They enter their name, their address, and their credit card details. With each click, they invest more time and effort. Only on the final confirmation screen does an obligatory “service fee” or “resort fee” appear, which was not disclosed at the start.

The user is now faced with a choice: abandon the transaction and “lose” the time they have already spent, or grudgingly pay the extra charge.

This design is a brilliant and cynical piece of manipulation. It works by exploiting a well-known cognitive bias: the “sunk cost fallacy.” Because the consumer has already invested resources, time and effort, they feel compelled to continue, even after the terms have changed. Their autonomy has been voided.

This brings us to the keystone of this pillar: we must always ask, “Would they choose otherwise if…”

Would the user have clicked “book” if the full price was displayed on the first screen? Perhaps not. By strategically withholding vital information, the designer has not persuaded the user; they have coerced them by making their initial, autonomous choice an illusion.

The walls of the prison were, indeed, invisible.

Foreseeable Consequences: The Creator's Burden

This pillar shifts the burden of responsibility squarely onto the creator. We are liable not for all outcomes, but for all foreseeable ones.

Orson Welles’s 1938 “War of the Worlds” broadcast remains the quintessential cautionary tale. By intentionally simulating a live news bulletin, complete with panicked on-location reporters and baffled experts, Welles blurred the line between entertainment and emergency. The resulting public panic was not an unforeseeable accident. It was the predictable outcome of exploiting the existing fears of a war-primed audience.

Decades later, the British broadcast Ghostwatch repeated the experiment, using the trusted format of a live documentary to present fiction as fact, and it, too, generated mass hysteria.

These incidents are not mere creative trifles; they are the “experiments” that have already been run. Creators cannot retreat behind a veil of “unforeseen consequences” when the potential for harm is so well-documented. The regulations that now forbid simulated news are the scar tissue from these failures.

This is the core of the pillar. Assessing foreseeable consequences is the act of “red-teaming” your own work. It demands you examine the pre-existing beliefs, fears, and ideologies of your audience and ask a simple, severe question: “What is the predictable harm of this interaction?”

Intent is not a defense against a foreseeable consequence.

Exploitation: Architecture of Motivation

Every immersive environment is a “choice architecture.” The final pillar of the framework, Exploitation, forces us to confront the motivation behind that architecture.

Consider the contrast between a shopping mall and a casino. Both are meticulously designed, but to vastly different ends.

The mall, as writers like Joel Garreau have noted, is engineered for a benign commercial purpose. Walkways veer to obscure distance, encouraging discovery. Glass elevators are used to make shoppers feel safe. “Landmark” department stores are placed to pull consumers deeper into the space. The goal, while commercial, is a straightforward value exchange: to create a pleasant environment that facilitates discovery and trade.

The casino uses the exact same principles for a darker purpose. It, too, uses confusing layouts, removes visual cues to the outside world (like clocks or windows), and provides landmarks. But here, the design is not facilitating discovery; it is encouraging disorientation.

This is where the architecture becomes exploitative. The casino couples this disorientation with known human vulnerabilities. It adds financial risk, provides alcohol to lower inhibitions, and deploys clever game design that intentionally fosters an illusion of control or skill.

These tactics are not designed to persuade a rational mind. They are engineered to bypass rational thought, exploiting cognitive biases to create a one-sided exchange. This is the essence of exploitation: it is not persuasion, it is prey. It occurs when an experience is designed to target a vulnerability, be it fear, guilt, addiction, or a manufactured illusion, for the designer’s gain.

Regulation, inevitably, follows this harm; it is the legislative scar and societal response to systemic exploitation. The ethical creator does not wait for it. They have the foresight to ask the severe final questions:

“Am I persuading, or am I preying?”

“Will I be seen as persuading, or seen as preying”

A Foundation to Build On

These four pillars: Consent, Autonomy, Foreseeable Consequences, and Exploitation: are not a creative checklist. They are the load-bearing walls of ethical design. They form the non-negotiable foundation that must be in place before we can earn the right to shape perception.

With this ethical architecture established, we can turn our attention to the mechanics of perception itself, an inquiry that brings us to the magician’s stage.